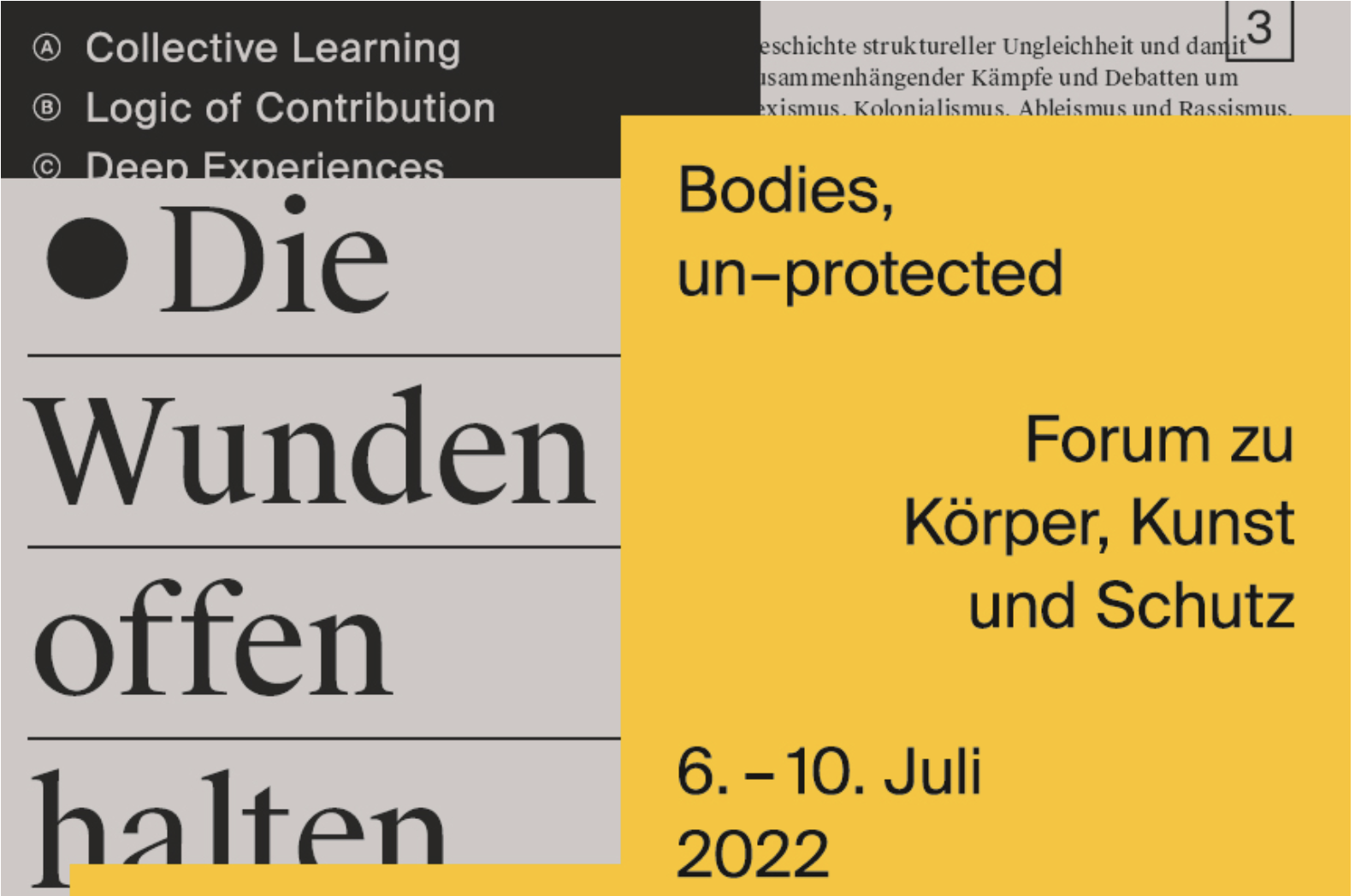

On Rending Bodies Invisible

a contribution to the publication of the project, “Bodies, un-protected”, 2022

“Bodies, un-protected” was initiated by Mousonturm and curator Sandra Noeth before the Covid-19 pandemic broke out – an experience that has placed the question of what various different bodies need to be considered worth protecting or receive protection at the centre of our society. At the same time, the lengthy history of structural racism and discrimination and current disputes about sexism, colonialism and ableism make it clear how urgently the protection of bodies needs to be negotiated across national and disciplinary boundaries: which bodies are worth protecting (to us)? Which bodies receive our support as individuals and as a community? Which bodies are able to appear on their own behalf, together with their specific needs and requirements, rather than purely as representatives of an often anonymous, stereotypical collective?

(The below text contains graphic details of torture, abuse and persecution of others. Content might be upsetting for some readers)

This text functions as a multi-purpose source, offering historical evidence, reflections, exercises, and personal anecdotes all attesting to the experience of being an “un-protected” body. Violability always being constitutive of any queer experience.

Anecdote (1)

I sat naked on the bed, my hands crossed as I placed them on my lap, my head bowed down a little. They refused to give me my clothes, and I wasn’t sure how serious they were in actually using violence. One of them had a pocket knife, the dull side of its blade, he ran across my face, saying he wouldn’t mind rearranging my face with it. The threat was menacing, exasperated and performative. Part of my thinking wanted to ask him, to egg him on, to see how could they deal with the physical mess facial wounds would leave (“for who could have thought the old man would have had so much blood in him!). But I was, in truth, terrified. Not because I didn’t want my face mangled by a sharp knife, rather the other threat, the threat of sending a video of me having sex with a man to my entire list of friends and contacts. The experience of vulnerability was not instigated by the fact that someone filmed me without my consent, but rather that they snatched my phone forcing me to expose all my personal data to complete strangers, who immediately wanted to use it to the full force of blackmail and extortion. It is difficult to think that consensual intimate acts between adults could have such potential for stigma and moral condemnation. But rationalising with three petty criminals about the virtue of agency and choice or the right to one’s body would not have got me too far. And probably would have incensed them to actually mangle my face or even slice up other parts of my body.

Excerpt (1)

[“Over six months, the men’s names made headlines while their faces stared from newsstands. Homosexual conduct drew unprecedented, censorious, and salacious attention. Fifty-two men were tried before an Emergency State Security Court, one boy before a juvenile court. All were charged with the “habitual practice of debauchery,” and nearly half convicted. Most of the men had been tortured in detention. The lives of all were ripped apart.”] p. 22

[“They beat us with a hose from a shisha [water pipe] and a baton with a big head. Everyone was beaten. They had our IDs: they’d call your name, and you would go up, and they beat you. I got beaten by the baton and from a hundred hands. I can’t tell for how long. You could feel the time when it flowed, but while I was beaten, time stopped.”] p.33

[“I told the prosecutor I’d been beaten. I showed him whip marks on my back and on my finger. The prosecutor said to his clerk, ‘Write that the accused came before us

wearing a vest’—he rattled off all my clothes—‘and that we found no injuries.’”] p. 37

[ “Then we were beaten. The policy is not to have the guards beat prisoners, so they can’t be sued, but to have other inmates beat prisoners. Many other prisoners participated in the beating.”] p.38

[“The door was closed for an entire month. We were isolated in the room. They just opened it to give us food and collect garbage. There was no running water almost all the time... We used to have fights for the right to use the bathroom and wash clothes. We only had one blanket to sleep on, on the floor. We put our shoes underneath our heads as pillows, and wrapped ourselves in the blanket for warmth.” For the first month the prisoners had no visits, letters, packages, or communication with their families. After weeks, the cell doors were allowed open for two hours daily—one hour at the beginning, one hour at the end of the day. Yet the prisoners were never allowed into the open air, only to stand in the corridor”] p.38

Excerpts from “In a Time of Torture: The Assault on Justice In Egypt’s Crackdown on Homosexual Conduct.”Human Rights Watch. 2004.

Exercise (1)

(For the purpose of this exercise, participants have to imagine that they are in a context where gender fluidity does not exist. Strict sex binaries have to be followed. Such is the reality of authoritarian societies)

-Imagine you took a date (at this stage of this exercise, imagine it was someone of the opposite sex) somewhere quiet and with potential for privacy, maybe a public park, or maybe even your house.

-Now imagine someone walks by (or walks in your room) and sees you being intimate with that person.

What would be this person’s reaction?

-Would a simple act of intimacy be grounds for someone to report you to the local authorities or the police?

-Does it involve any kind of threat or bodily harm to you and your date?

-Does it involve possible legal consequences for you and your date (arrest/detention/possible prison time)?

-Do you think it is possible that someone might want to end your life because you kissed someone of the opposite sex?

-Would such exposure involve public stigma, shame, or compromise of your social standing in your community?

-Now imagine your date is a member of the same sex, and someone sees you being intimate in the same way.

Will the answers to those questions be the same?

-Now imagine you and your date (of the same sex), are attacked, injured and arrested with a potential prison sentence of up to seven years (even if you are both minors).

Do you think you would still, after such an experience, go out on a date or try to seek similar opportunities for romantic intimacy just the same?

Reflection (1)

The neoliberal paradox that started taking shape over the past four decades took savage proportions in the global south. The scaling back of the social function of the state (the social security networks and programs meant to counterbalance the worst failings of capitalism) while expanding its surveillance and policing function meant that by the 1980s the social contract of post-independence (authoritarianism in exchange for basic living standards) has been unilaterally revoked, with an ever-privatised economy that consistently kept disinvesting in basic public programs (education, health, infrastructure,...etc). Parallel to a degree of securitization that at some point saw almost 3% of the population joining the Ministry of Interior in different capacities, turning Egypt into nothing more than what one activist called “an abattoir for torture”.

This begs the question of what is the state beyond its monopoly over violence? And when citizens are seen rather as liability, a potential threat to the state, a threat that requires an ever-increasing degree of paranoid surveillance and irrational violence, how does that reflect on the value and worth of those citizens within a global community? If the state sees its citizen as liability to be coerced, controlled and constantly punished, then in a world of asymmetrical power relations and obscene inequalities, we, as ‘third world’ citizens are seen as nothing more than a threat, a nuisance, to be also be dealt with, by extension, as a liability to the rest of the world, to be avoided, exorcised, and obliterated if must.

Exercise (2)

This exercise requires 4 participants role-playing a particular scenario.

Participants:

Participant (1): refugee (from the MENA region) is a visibly gender non-conforming gay man

Participant (2) refugee (from the MENA region) is a typically social conservative cisgendered heterosexual man

Participant (3): Observer (white)

Participant (4): Police officer (white)

Place: Anywhere in Western Europe

Time: Any point in time over the past decade

The exercise unfolds as follows:

Participant (2) is going to simulate a physical attack on Participant (1) because he is offended a fellow citizen/national is threatening long-held cherished beliefs about conventional gender and sexual norms

-Participant (1) will try to resist and remind Participant (2) that in the context of Western Europe, personal freedom trumps individual norms of social conformity

- What do you think are the possible roles for participants (3) and (4) at this point?

-Participants are invited to play out all the different possibilities and record the different outcomes

-Participants are then going to look up actual incidents in their respective countries (or other countries in Western Europe) where harassment among refugees - due to perceived difference in gender expression and sexuality - took place.

-Of all the role-played scenarios, which one was the closest to reality?

Excerpt (2)

[Another rights lawyer.. described an incident.. He asked the prosecutor about individuals arrested on debauchery charges “but the prosecutor did not deign to answer me, instructing an administrative employee to answer my questions instead. The assistant took me to a staircase where 16 women arrested on prostitution charges were piled on the stairs, waiting for their turn to see the prosecutor and the assistant told me, ‘You have all these women, pick one to defend for free, and you can do your little number, then the girl will do what you want, or do you have a thing for faggots?”] p. 26

[The court decisions are also rife with invocations of religious and ethical values that disdain homosexuality and denigrates it, even if the evidence in the case is weak and the court procedures are faulty. This is the text of a verdict in the previously mentioned.. case:

“The court arrived at the conviction that the defendants committed the crime of debauchery, which has been established with certainty by catching them with women’s clothing and make-up in their possession, in addition to the womanly conduct of the defendants that the court has observed. The prophet has said, ‘God curses men who dress like women.’ Homosexuality is a transgression against humanity and contravenes nature hence God has made it a major sin, even more licentious than adultery.]” p.36

Excerpts from, “The Trap: Punishing Sexual Difference in Egypt”. Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights. 2017

Reflection (2)

With the exception of higher courts of appeal (known for their measured and sophisticated judicial perspective), the general prosecution and courts of first instance in Egypt are always deeply at odds with so-called obscenity crimes and crimes infringing on public morals. An unhappy mix of vague, doctored up religiosity and deeply conflicted and anxious patriarchal angst permeates the entire language, discourse and decisions that both organs of justice produce and enact. It becomes less and less about arbitrating between a presumed transgression against the law and the public and rather a spectacular (for it becomes a spectacle) opportunity to use the dramaturgy of litigation and adjudication to punish perceived difference and mark it as “the public enemy” par excellence. An act of scapegoating that reinforces existing subjection of every possible marginalized group while offering insecure heterosexual men a platform to sermonize and enjoy a moment of near-ecstatic pietistic affirmation.

Anecdote (2)

The Border Control officers refused to answer any of my questions. I was not sure if that was due to the fact they did not speak English or out of maintaining that air of forced, fictitious seriousness. I thought it would be very unlikely that in the capital of the EU headquarters, border control officers would not be able to speak English. Feigned sense of sternness it is then. I was escorted to a room where other “problematic” passengers were kept. An elderly Turkish lady was sitting on the floor, along with other companions (maybe her family?). She looked kind and motherly, and she kept smiling and talking to me in Turkish, and I could only stare back, trying to hold on to a certain sense of familiarity in that strange space. I was asked to sit along a row of seats. As I sat, there was a plaque right above my head. I noticed it bore the emblem of the EU. I became curious and turned my head, and strained and looked up. It was a quote from the European Convention on Human Rights, Protocol No.7, regarding the expulsion of aliens. I immediately started laughing. And I looked at the Turkish lady, who, amused by my sudden change of spirits, smiled along, for laughter was the only response to the moral hypocrisy permeating everything around. The violent dissonance between the mandates of law, and realpolitik is always manifested in undesirable bodies.